International Conference: Teaching and Learning Arabic K-16

Join Arabic language experts and enthusiasts from around the world for a conference on research, teaching practices and innovative approaches for Arabic speakers in educational settings.

Violence has erupted in Sudan as the two major militarized groups, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), have gone head-to-head in civilian-populated areas. With casualties rising and no resolution in sight, News@AUC interviewed two faculty members from the Department of Sociology, Egyptology and Anthropology, Assistant Professor and Associate Researcher Amira Ahmed and Assistant Professor Manuel Schwab, to explain the conflict, its impact on Sudanese citizens and what the international community can do to help.

Causes of Conflict

The current fighting is the culmination of decades of turmoil in Sudan, but its most recent causes can be traced to Sudan’s 2019 revolution, which toppled former President Omar al-Bashir and briefly replaced him with a civilian government.

“The Sudanese people were aspiring to remove a military fascist regime that had governed the country for 30 years,” explains Ahmed, who is a daughter of Sudanese immigrants living in Egypt. “Al-Bashir originally legally recognized the RSF to suppress rebellions on his behalf, but the leader of the RSF turned against al-Bashir when the revolution began.”

The 2019 revolution was successful in deposing al-Bashir but left a power vacuum in its wake. A civilian government ruled briefly but was quickly sidelined by the RSF and the SAF. While the two groups had collaborated to bring down the former regime, governing the country afterward proved controversial.

“The RSF was supposed to be integrated into the SAF, which would have created a unified army. That was Omar al Bashir’s plan to maintain power,” says Schwab. “But the integration was not completed by the time he was removed, leaving two groups competing for control who eventually turned on one another.

This scramble for power has proven catastrophic for Sudan as violence rules in the capital, Khartoum, and fighting is spreading throughout the country. The death toll on May 9 had risen to 604 according to the UN health agency. However, an accurate number of casualties may be higher due to complications with reporting. The severity of the conflict reminds some of the genocide in Darfur in 2003, during which the RSF killed between 80,000 and 400,000 people and displaced nearly 3 million at the orders of al-Bashir.

Power of the People

This echo of history raises the question: After the successful, civilian-led revolution in 2019, how has the country descended into levels of chaos that have not been witnessed since 2003?

“The revolution in 2019 showed the incredible organizing capacity, tenacity, commitment and grassroots solidarity of Sudan,” states Schwab. “I believe Sudan is a place where the power has always been with the people. Unfortunately, the force has always been with the militaries and these groups took over the revolution for their own goals.”

The citizens of Sudan are keenly aware of the role of these armed forces in destabilizing their country. “The Sudanese people are calling for the SAF to go back to the barracks and the RSF to be dissolved,” Ahmed explains. “The people want a democratic civilian government, but first they need the violence to stop.”

Human Impact

According to the United Nations, there are currently 4.3 million people in South Sudan who need humanitarian assistance, but the raging violence is making it difficult for supplies to be distributed. Additionally, nearly 2.3 million refugees from South Sudan are currently displaced and 63% of these refugees are children.

“People are dying from more than just bullets and bombs,” says Ahmed. “They are dying from a lack of food, medicine and water. They are dying from preventable diseases or injuries because their hospitals have been destroyed or occupied by armed forces.”

Egypt is a major location for Sudanese refugees to flee to, but supporting them is a difficult task. Ahmed and Schwab attempted to create a GoFundMe campaign to generate funds for arriving refugees, but the campaign was suspended within 72 hours. According to Ahmed and Schwab, this Is symptomatic of the financial distrust that is directed at Sudan.

Sanctions Are Not a Solution

“I will never understand why the international community does not pay attention to the terrible effects of financial and goods-based sanctioning on the Sudanese people,” says Schwab. “There is no evidence that sanctions have any influence on the decisions of these gold-rich governing elites, but there is plenty of evidence that they do real harm to civilians.”

According to Schwab, there is a contradiction between two cornerstones of international relationships with Sudan since it gained independence. The international community executes harsh sanctions to pressure the regime by squeezing its citizens while simultaneously providing humanitarian aid that is meant to offer relief. Together, the two produce a situation in which scarcity and need can be manipulated by various actors, international or domestic, leaving the people of Sudan to pay the price.

This allows the international community to appear invested in solving the problem, without addressing the core issue: International policy regards Sudan as a security problem, not a human catastrophe.

“International powers all see Sudan as a security threat, so they are more interested in ensuring stability than creating long-lasting peace. They want to back the right warlord who will keep Sudan managed, not help the Sudanese people build a civilian democracy,” he says.

The Way Forward

“We have to rethink the way the international community treats Sudan and must listen to the voices of Sudanese people,” says Ahmed. “We need to find a way to stop the violence, but allowing either the SAF or the RSF to rule the country will only lead to a military dictatorship. That may answer the security problem, but it won’t help bring peace to the people.”

Additionally, humanitarian aid needs to be expanded and sanctions rescinded, Schwab recommends. “We need to open up more channels for humanitarian aid alongside corridors of mobility for people to escape. We also need to communicate to our home governments that we do not support sanctions as a solution,” he says.

“Don’t forget Sudan,” Ahmed concludes. “Sudanese people are some of the most politically engaged in the world, but they need the safety and opportunity to build a peaceful future."

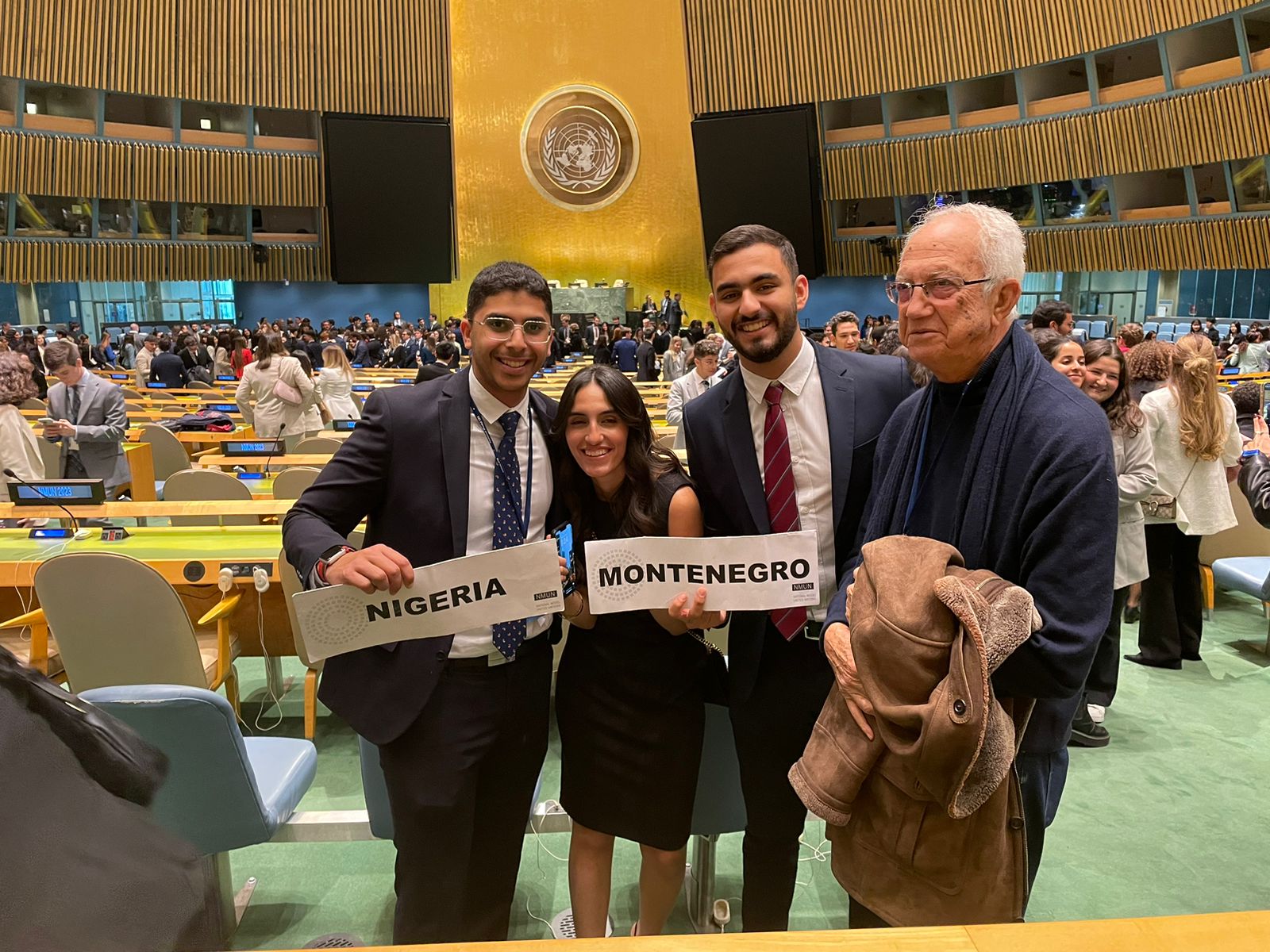

Debate your hearts out! AUC’s Cairo International Model United Nations (CIMUN) swept the National Model United Nations in New York last month. Representing Nigeria and Montenegro, the 37-person team took home an impressive 14 awards, making AUC the most-awarded university at the conference.

Within those achievements, the team won two Outstanding Delegation Awards — the highest award a university can achieve— for their group representation of Nigeria and Montenegro. In addition, the AUC delegates won 12 individual awards across multiple councils, including the Human Rights Council, General Assembly, UN Environment Assembly, UN Economic Commission for Africa, International Atomic Energy Agency, Commission on the Status of Women, and Commission Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice.

"The amazing team of delegates we had this year led AUC to become the university with the highest number of awards at the NMUN conference this year, as well as the only university to receive not just one but two Outstanding Delegation Awards. I believe this team raised the bar for many years to come," said Ali Hussein, economics major and CIMUN organization committee head.

Getting ready for this conference took more than six months of practice and a rigorous selection process that included interviews as well as mock conferences and position paper writing. The preparation phase comprised general training sessions for the delegation overall as well as more specific training and strategies for the different councils, in addition to researching foreign policy and identifying key international agreements to support the team's stance. There were also simulations to fully prepare the team for all aspects of the conference as well as a comprehensive process for writing the position papers, "which is a very important aspect of the NMUN conference and yielded many awards for us," explained Hussein. "This year, the majority of our delegates were freshmen and had never experienced a conference of this scale before. This made the preparation process longer and more challenging, which made the victory at the end even more rewarding. That was what was most special about the CIMUN victory this year."

Farid Hani, economics major with a minor in international relations and CIMUN undergraduate academic adviser, echoed similar sentiments. "Working with each and every one of our delegates in training, selection and writing position papers builds a personal connection, and we were eager to see them shine in action. Indeed, they passed our expectations and demonstrated great leadership, presentation, research, analytical and diplomacy skills," he said, adding:

"This year marks the 35th CIMUN team, and it was our target to truly make an impact and prepare the next generation of leaders to partake in this rigorous and prestigious conference. What really made a difference despite our delegation's young age was their spirit, dedication and eagerness to learn. To me, seeing their hard work come into play and their development over the months of training was the true victory."

Walid Kazziha, political science professor and CIMUN's faculty adviser, commended the hard work put in by all those involved. "My sincere thanks goes to all colleagues and staff members who helped prepare CIMUN for its great success," he said. "Above all, we owe our students and their High Board a word of gratitude and true recognition for the relentless efforts they have made to maintain the high standards we always demand of them.”

For participating students, the conference taught them valuable lessons both personally and professionally. "Attending the NMUN conference this year as head delegate has taught me a lot of new skills and lessons," reflected Hussein. "The key lesson I learned was how to properly strategize and plan ahead with my fellow High-Board members in order to reach the best outcome possible, which we thankfully succeeded in doing. Other important skills that were reinforced, thanks to this experience, included discipline, leadership and diplomacy. I am now assured that if I put my mind to something, plan accordingly, trust the process –– and most importantly my team –– I will reach the goal that I had set out from the beginning."

As Lara Radwan, economics major and CIMUN secretary-general put it, "Year by year, our goals for NMUN increase, and this year, we were able to win the highest amount of awards amongst all competing universities. With the competition becoming stronger and the MUN scene growing day by day, we had to prepare our team to become the top competing university in this year’s conference. The process has definitely been challenging, but the amount of knowledge we gained en route and the experience of getting to meet participants from all over the world is indescribable!"