Teaching Arabic as a Foreign Language: Dalal Abo El Seoud

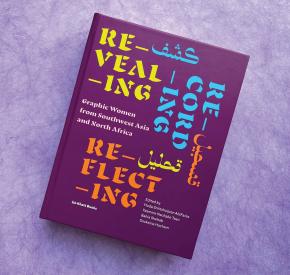

Effective methods of teaching Arabic as a foreign language (TAFL) incorporate both communication and creativity to address the complexities of the Arabic language. Exploring this topic, Dalal Abo El Seoud, senior instructor II in the Department of Arabic Language Instruction, most recently edited the newly released book, Challenges in Teaching Arabic as a Foreign Language (AUC Press, 2024), which brings together the expertise of 18 TAFL professionals.

We spoke with Abou El Seoud to learn more about the challenges that TAFL instructors and students face, her motivation for editing the book and what she hopes readers will take away from it.

1. What are the common challenges that non-native speakers of Arabic face when studying the language?

Students studying the Arabic language face several difficulties, including pronunciation and the Arabic script itself, which differs significantly from the Roman alphabet. The complexity of Arabic grammar, vast vocabulary, and reading comprehension can be daunting. In addition, Diglossia, the coexistence of Modern Standard Arabic and regional dialects, can create communication difficulties. Understanding the cultural and historical context linked to Arabic can also be time consuming.

2. What do you believe motivates non-Arabic speakers to learn the language?

Some are motivated by cultural interest, seeking to understand the rich tapestry of Arabic culture. Others are compelled by religious reasons, with many Muslims worldwide studying it for a more profound connection to their faith. Some are also drawn to it for professional and academic opportunities –– whether travel, communication, humanitarian efforts or personal relationships.

3.What is the best way to teach Arabic to non-native speakers?

The ideal teaching approach should be eclectic and student-centered, creating an enjoyable learning environment through interactive games and engaging activities. It should focus on clear learning outcomes for each lesson and put together multiple assessment measures to ensure student comprehension and progress.

4. What motivated you to edit Challenges in Teaching Arabic as a Foreign Language?

My profound passion for the Arabic language and strong desire to share its beauty and significance with others. I want to create a valuable resource that fills a noticeable gap in the existing TAFL literature. By offering practical insights and guidance, I hope to not only contribute to the field of language education but also promote cross-cultural understanding.

5. What was the most challenging part?

Ensuring grammar and style consistency, preserving the author’s voice, handling citations, managing deadlines and providing constructive feedback to authors.

6. What’s the most valuable benefit you gained from editing this book?

This experience has not only deepened my knowledge but also expanded my professional network. I derived benefit and inspiration from each and every chapter. Whether it was insights into educational methods, discussions on cultural sensitivity, examinations of emerging trends or nuanced approaches to assessments, every chapter offered valuable perspectives that deepened my appreciation of the subject matter. It was truly a holistic journey of learning, and the synergy of all these facets within the book left a profound impact on me.

7. What can readers expect to gain from the book?

The book can highlight some of the challenges that teachers face when teaching Arabic as a second language and offer practical solutions and effective strategies to address them. It can provide insights into instructional techniques, materials, and activities that have proven successful in Arabic language classrooms. It can also inspire further research and academic advancement in understanding the challenges and effective practices in teaching Arabic. In addition to that, researchers and scholars can benefit from the book as a resource for literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and ideas for future research directions.

8. What about the instructors featured in the book?

All of them have extensive experience in teaching students of Arabic as a foreign language over an extended period. Their collective wisdom and years of dedicated teaching have equipped them with a profound understanding of the challenges and nuances that non-native students encounter. Their longstanding commitment to the field makes their contributions to this book particularly insightful.

9. What advice would you give other TAFL instructors and teachers-in-training?

Opting for continuous engagement in ongoing research and new teaching methodologies to implement in the classroom, as well as being proactive in creating diversified assessment techniques that would provide students with hands-on learning experiences. This commitment to staying abreast of the latest educational advancements not only maintains their teaching dynamic but also enriches the educational journey of their students.