<?xml encoding="UTF-8">

EWART MEMORIAL HALL

In 1925, an anonymous donor offered AUC a gift of $100,000 for the construction of a 1,150-seat auditorium. She requested that the auditorium be named after her grandfather William Dana Ewart, who had in the past visited Egypt for health reasons. Since then, Ewart Memorial Hall has housed musical and theatrical events, including Egypt's renowned singer Om Kolthoum and AUC's own Osiris Singers. Egyptian presidents have attended events at the hall, and in the 1970s, when the Cairo Opera house burned down, it became one of the venues for the Egyptian opera and ballet.

HILL HOUSE

AUC Tahrir Square campus, downtown, October 2016.

Hill House was named after William Bancroft Hill and his wife Elise Weyerhaeuser Hill. William Bancroft Hill served on AUC's Board of Trustees for almost 25 years, including 20 years as chairman. Hill House started as a student dormitory when it was first opened and later became AUC's main library in 1959, holding 60,000 volumes at the time. It was remodeled in 1984 to house the University bookstore, classrooms, offices and meeting rooms. The Weyerhaeuser family, who donated $150,000 for the original construction of the building that opened in 1953, also financed Hill House's remodeling, which was completed in 1986.

TAREK JUFFALI ENDOWED FELLOWS PROGRAM

Suad Juffali, AUC advisory trustee and chair of the Ahmed Juffali Foundation, established the Tarek Juffali Endowed Fellows Program in counseling psychology and community psychology and named the Tarek Juffali Professorship in Psychology, both in honor of her late son. She also established the Suad Al-Husseini Juffali Scholarship for students from Palestine and named the Serenity Room at the AUC Library and La Palmiera Lodge female student dormitory, among many of her generous contributions. She received the Global Impact Award in 2017 from AUC for her leadership in philanthropy.

BARTLETT FAMILY LEGACY

The Bartlett family has a long tradition of giving to AUC. Thomas Bartlett, who served as AUC president from 1963 to 1969 and as interim president from 2002 to 2003, has made numerous contributions to the University, most notably, establishing -- with his wife, Mrs. Mary Louise Bartlett -- The Bartlett Room student lounge at AUC New Cairo.

Sharing his father's passion for education and for AUC, Richard Bartlett, chairman of the Board of Trustees, has served as a trustee since 2003. Richard Bartlett has contributed significant time and energy to the University, as well as philanthropic support for numerous programs and scholarships. In 2011, he established the Molly Bartlett Endowed Scholarship in his mother's name to support top-performing Egyptian public school students who wish to attend AUC. He also contributed to the Access to Knowledge for Development Center. In 2018, Richard and his wife, Kerri Bartlett, gave $2 million to establish The Bartlett Fund for Critical Challenges, an endowed fund to encourage research and other projects that address defining challenges shaping Egypt and the region. Through this fund, AUC will play a leading role in developing creative responses to challenges, such as issues of sustainability, poverty, demographics, health, education, urbanization, water resources, governance and regional politics.

Richard and his brother Paul, both AUC trustees and Princeton University graduates, established the Bartlett Family Fund for Innovation and International Collaboration between AUC and their alma mater. The 150-meter-long Bartlett Plaza, a hallmark of AUC New Cairo and the principal outdoor location for AUC's largest events, including commencement and alumni homecoming, is made possible through a generous donation by Mr. and Mrs. Paul Bartlett. In addition, Thomas, Richard and Paul have all provided support for the Center for Arabic Study Abroad Endowment Fund.

JAMEEL: 'LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON'

In 1982, prominent Saudi businessman Abdul Latif Jameel donated $5 million, the largest gift that AUC had ever received at the time, to build the Abdul Latif Jameel Center for Middle East Management Studies and the Abdul Latif Jameel Chair in Entrepreneurship. Located on AUC's Greek Campus, the building accommodated the steady growth of the student body in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as well as the increasing demand for management, engineering sciences and other professional programs.

In 2009, Yousef Jameel '68 inaugurated the Abdul Latif Jameel Hall on the New Cairo campus in the name of his father. The building houses the School of Business and School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, in addition to the Kamal Adham Center for Television and Digital Journalism and The Photographic Gallery. A pioneer in his own right, he also established the Yousef Jameel '68 Science and Technology Research Center in 2003. At that time, there were no research facilities in Egypt capable of developing micro/nano devices. Jameel had the vision to create such a center of excellence at AUC in the field of nanotechnology, bringing together top-notch researchers and scientists from around the world.

Increasing access to quality education, Jameel launched the Yousef Jameel MBA Fellows Program in 2004. The program continued for more than a decade, with more than 150 graduates. He also funded the Yousef Jameel '68 GAPP [Global Affairs and Public Policy] Public Leadership Program, supporting 300 fellows in 12 cohorts of 25 Egyptian graduate students per year. When AUC's PhD program began in 2010, he initiated the Yousef Jameel '68 PhD in Applied Sciences and Engineering Fellowships. AUC's first PhD graduate, Yosra El Maghraby '04, '08, '14, was a recipient of this doctoral fellowship, which graduated more than 40 students.

Supporting Scholarships

ABDALLAH JUM'AH STUDY ABROAD SCHOLARSHIPS

Abdallah S. Jum'ah '65 served as president and CEO of the Saudi Arabian Oil Company (Saudi Aramco), the world's largest oil-producing company, from 1995 to 2008. He established the Abdallah Jum'ah Study Abroad Scholarships in 2015 to support undergraduate AUC students seeking a study-abroad experience for one semester in order to expand their horizons and broaden their cultural perspectives. He received a Global Impact Award from AUC in 2016 for his innovative approach to business and strong interest in developing leaders.

"Before joining AUC, I hesitated on whether I wanted to join AUC or study abroad. But during my freshman year, I realized that the opportunities that AUC offers are not to be found elsewhere. ... And the study-abroad [scholarship] opportunity only adds to this rich and versatile experience. AUC is preparing future leaders who understand a world beyond their own. We know what it means to compete on local and international scales."

Seif Hamed '17

Business Administration

MOHAMMAD ABUGHAZALEH '67 ENDOWED PALESTINIAN SCHOLARSHIP

Former AUC Trustee Mohammad Abughazaleh '67 has been serving as chairman and CEO of Del Monte Fresh Produce Company in Jordan for more than two decades. In 2006, he established the Mohammad Abughazaleh '67 Endowed Palestinian Scholarship at the University to support five deserving and talented Palestinian students. A total of 17 students have benefited from this scholarship. In 2005, Abughazaleh received the Distinguished Alumni Award from AUC.

"Thank you for believing in me and giving me this opportunity. You have helped me work toward accomplishing my goals and building my future."

Ayah Harhara, business administration

JOHN AND GAIL GERHART ENDOWED PUBLIC SCHOOL SCHOLARSHIP

Named in honor of AUC's late ninth President John D. Gerhart, the John and Gail Gerhart Endowed Public School Scholarship was established in 2002 to support talented students from Egypt's public schools. A recipient of an honorary doctorate from AUC in 2002 and the only president to hold the title of president emeritus, John Gerhart was a firm believer that an essential aim of a liberal arts education is to instill values of service and civic responsibility among students. More than 230 AUC friends have provided generous support to establish this scholarship in his name, including his wife, Gail Gerhart, who has made significant contributions to AUC.

"Thank you so much for giving me this opportunity. My time at AUC has completely changed who I am. I hope to take what I have learned and work to improve both my immediate community and entire country."

Mohamed Ibrahim

Electronics and Communications Engineering

ABDULHADI H. TAHER ENDOWED SCHOLARSHIP

The Abdulhadi H. Taher Endowed Scholarship supports Egyptian and Saudi Arabian students with outstanding academic performance. Currently, eight students are studying at AUC as recipients of this scholarship. Following in their father's footsteps, Nashwa and Tarek Taher have created transformative experiences for AUC students, including the Nashwa A. H. Taher Arab Women Scholarship in 2004.

"Thank you for giving me the opportunity to study at the most prominent institution in my country"

Nouran Barakat

Undeclared Freshman

MOHAMMED BIN ABDULKARIM A. ALLEHEDAN SCHOLARSHIP AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH FUND

Established in 2015 by the late Sheikh Mohammed Bin Abdulkarim A. Allehedan, the fund aims to support talented Arab students and encourage specialized scientific research in uncommon disciplines in the Arab world. As the late Allehedan put it, "I come from a modest family, and I didn't get the chance to be educated. After researching, I found that the best place for me to put this endowment would be at a university in Egypt, and I found that The American University in Cairo is the best University in Egypt. ... I am one of the believers that Arabs would not exist without Egypt, and Egypt would not exist without Arabs. And if Arabs are not well-educated, they will not be strong."

"As both a student and a member of the research community at AUC, I would like to thank [Sheikh Allehedan] for his support of innovative research. That support will allow us to have strong academic careers and give us opportunities to develop our skills."

Ahmed El Sayed '15 '17

Pursuing a PhD in Applied Sciences at AUC

AL GHURAIR STEM SCHOLARS

Supported by Abdulla Al Ghurair Foundation for Education, one of the largest privately funded philanthropic education initiatives in the world, the Al Ghurair STEM Scholars program creates opportunities for underserved, high-achieving Arab students to pursue an undergraduate or graduate degree at leading universities in the region, including AUC. Launched in 2016, the program has supported more than 150 students at the University, helping them pursue their dreams of a high- quality STEM education. With a Master of Science in nanotechnology, Menna Hasan (MSc '18) is the first AUC alum of Al Ghurair STEM Scholars Program.

"This scholarship has been a dream, getting a chance to travel outside of Yemen to receive a proper education. Getting a scholarship, what can I say, it's like a passport in my life. I can never thank the foundation enough. Never."

Mohammed Al-Sabri

Mechanical Engineering

By the Numbers

Since the 1970s, more than $100,000,000 has been raised to support scholarships and fellowships.

Approximately $630,000,000 financial support given to students since 1975.

More than 3,000 students per semester have received any form of financial assistance in the past five years.

Approximately 6,000 donors since the 1970s.

Yousef Jameel '68 is AUC's single biggest supporter of education, funding research as well as master's and PhD fellowships.

AUC'S TOP DONORS IN THE PAST 100 YEARS

$5 MILLION+

Abdulla Al Ghurair Foundation for Education

Sheikh Faisal Kamal Adham

Dr. Khalaf Ahmad Al Habtoor Hon LHD

Sheikh Mohammed Bin Abdulkarim A. Allehedan*

Dr. Sarwat Sabet Bassily*

H.R.H. Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Alsaud Hon LHD

Mr. Mohamed Shafik Gabr '73

Sheikh Abdul Latif Jameel Hon LHD*

Mr. Yousef Abdul Latif Jameel '68, Hon LHD

$1 MILLION+

Abraaj Group

Mr. J. Dinsmore Adams, Jr.

Sheikh Kamal Adham*

Mr. and Mrs. Moataz Al Alfi

Dr. Hamza Bahey El Din Alkholi

H.H. Sheikh Dr. Sultan Bin Mohammed Al-Qasimi Hon LHD

Sir Nadhmi Shakir Auchi

Mr. Theodore S. Bacon, Jr.*

Mr. and Mrs. Paul H. Bartlett

Mr. Richard and Mrs. Kerri Bartlett

BP USA

Dr. Barbara Brown and Dr. Steven C. Ward

Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Cashin

Commercial International Bank (Egypt)

Paul I. and Charlotte P. Corddry

Mr. Miner D. Crary, Jr. and Mrs. Mary Crary*

Mrs. Mary Cross*

Mr. Hassan '73 and Mrs. Jill Dana

Mrs. Elizabeth S. Driscoll

Mr. Hesham Helal El Sewedy '88

ExxonMobil Corporation

Mr. Paul B. Hannon Hon LHD

Dr. and Mrs. Elias K. Hebeka

Dr. and Mrs. Ahmed M. Hassanein Heikal

HSBC Bank Egypt S.A.E.

Mrs. Hadia Abdul Latif Jameel

Mrs. Suad Al-Husseini Juffali Hon LHD

Louise Moore Pine Trust

Mr. and Mrs. Bruce L. Ludwig

H.E. Mr. Mohamed Loutfy Mansour

Mr. Hatem Niazi Mostafa* and Mrs. Janet Mostafa

Mr. Youssef Ayyad Nabih*

Sheikh Abdul Rahman Hayel Saeed '68

Saudi Arabian oil Company (Saudi Aramco)

Schlumberger Stichting Fund

Sheikh Mohammed Wajih Hassan Abbas Sharbatly '89

Dr. William K. Simpson Hon LHD*

Dr. Abdulhadi Hassan Taher*

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

The Ford Foundation

The Selz Foundation

The Tokyo Foundation

*Deceased

Hon LHD Honorary Degree

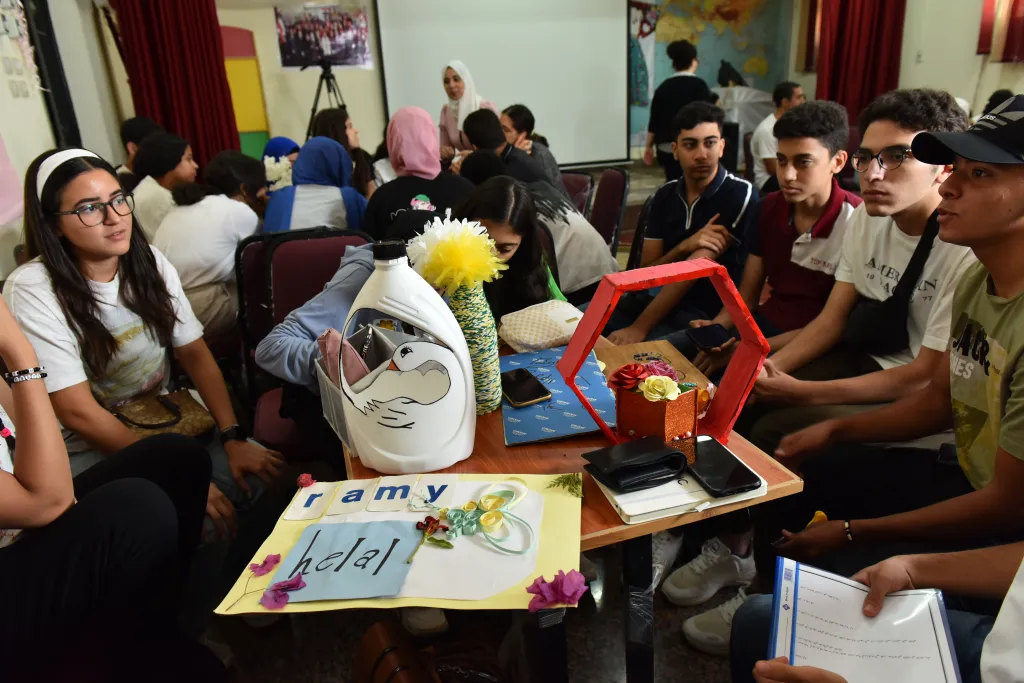

Laila El Baradei with Public Policy Hub members, photo by Ahmad El-Nemr

Laila El Baradei with Public Policy Hub members, photo by Ahmad El-Nemr

Sameh at AUC New Cairo, photo by Ahmad El-Nemr

Sameh at AUC New Cairo, photo by Ahmad El-Nemr The card game, Share, photo by Ahmad El-Nemr

The card game, Share, photo by Ahmad El-Nemr

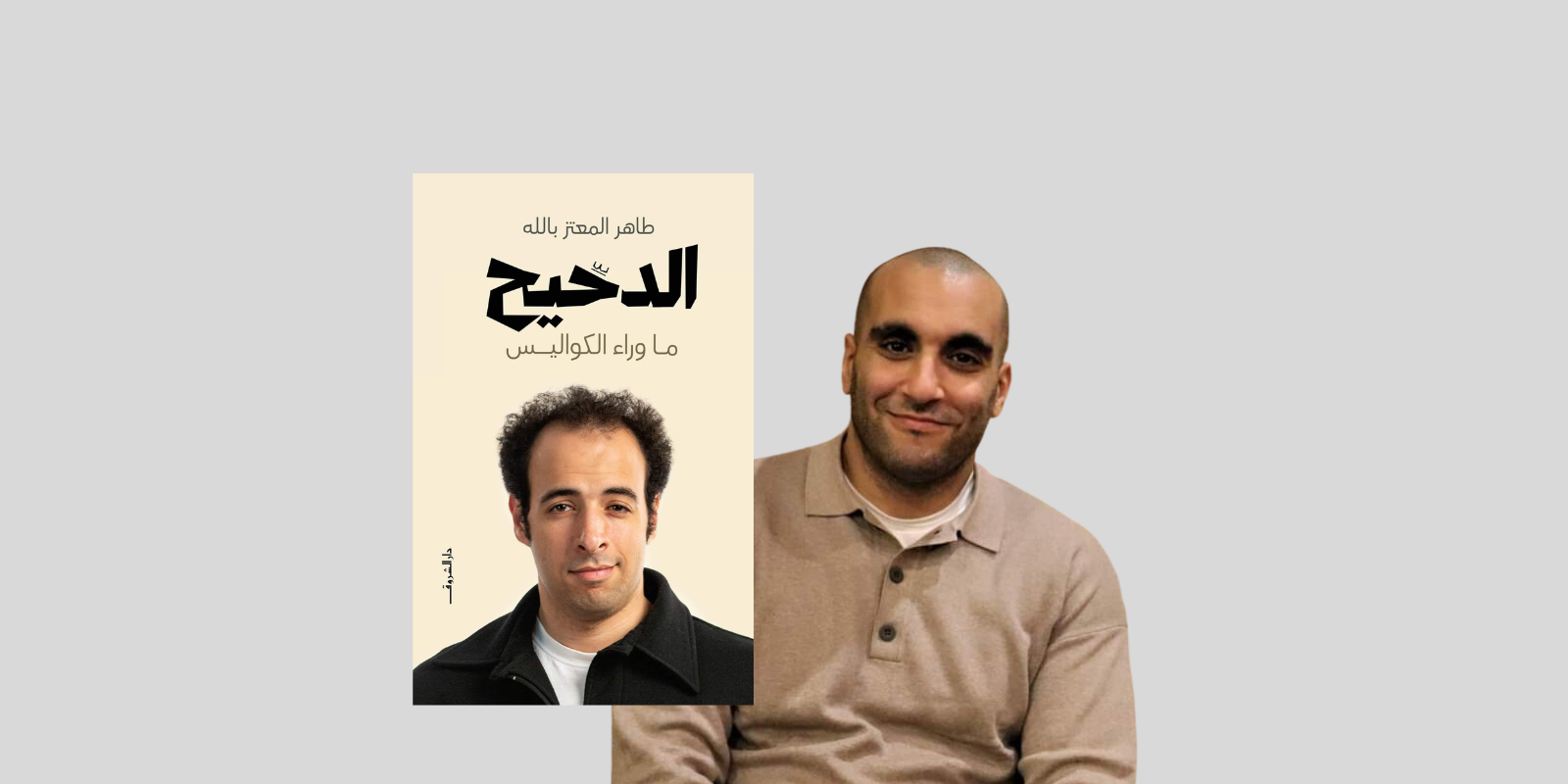

Taher El Moataz Bellah

Taher El Moataz Bellah

Dina Heshmat. Photo by Ahmad El-Nemr

Dina Heshmat. Photo by Ahmad El-Nemr

Mansoury and ElSoueni hope to expand Rabbit's operations outside of Egypt

Mansoury and ElSoueni hope to expand Rabbit's operations outside of Egypt

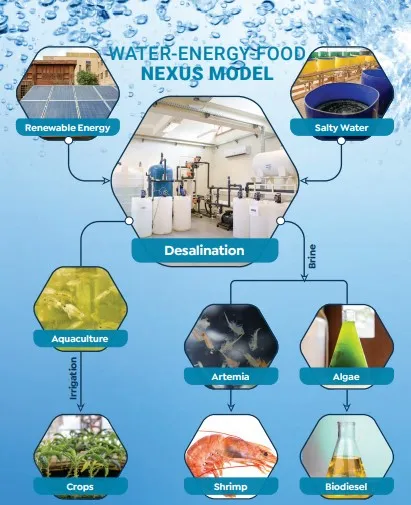

Sewilam: "The sky is the limit. This could be the next food production revolution." Photo by Ahmad El-Nemr

Sewilam: "The sky is the limit. This could be the next food production revolution." Photo by Ahmad El-Nemr