Architects

Architectural Vision

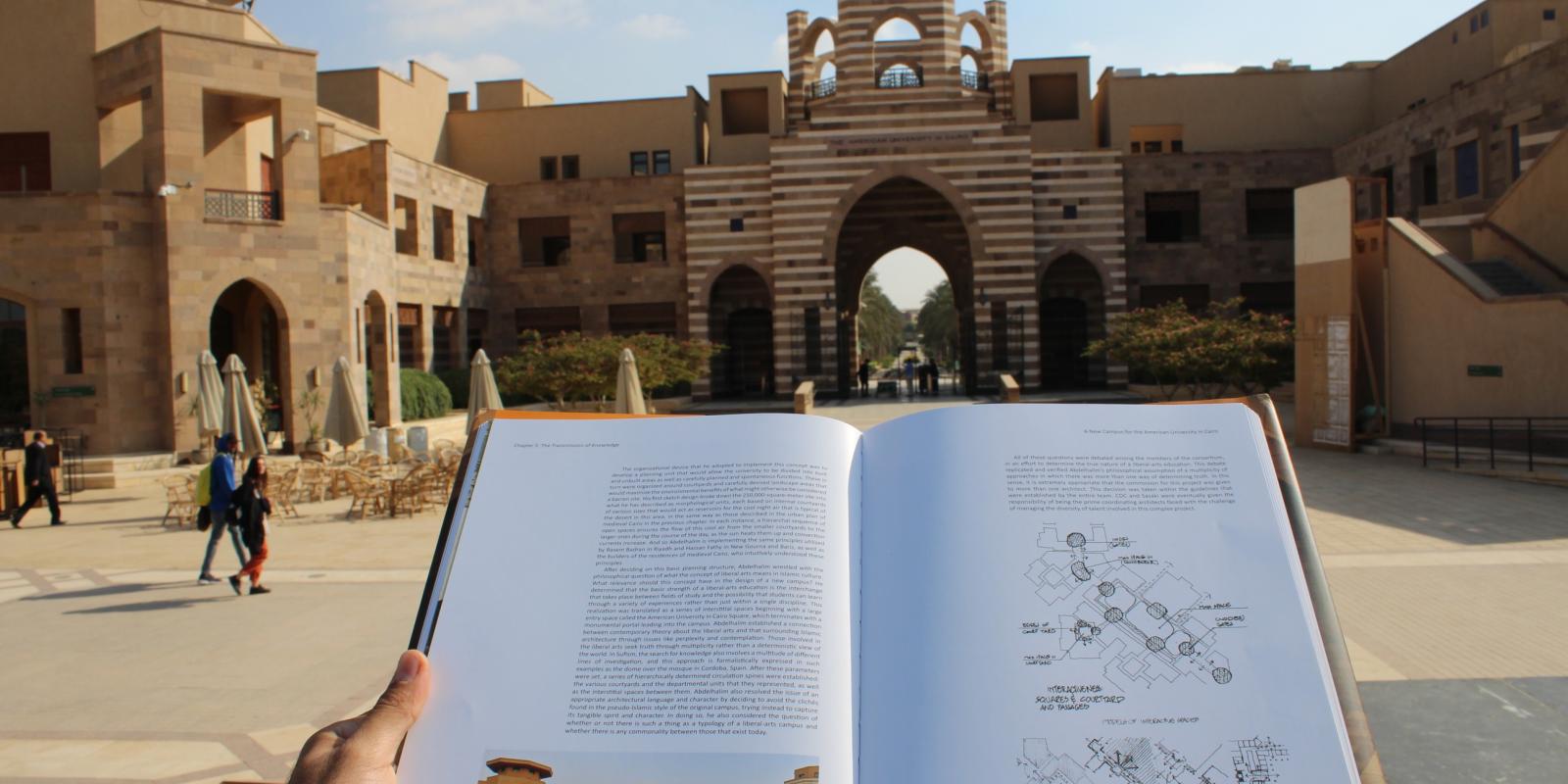

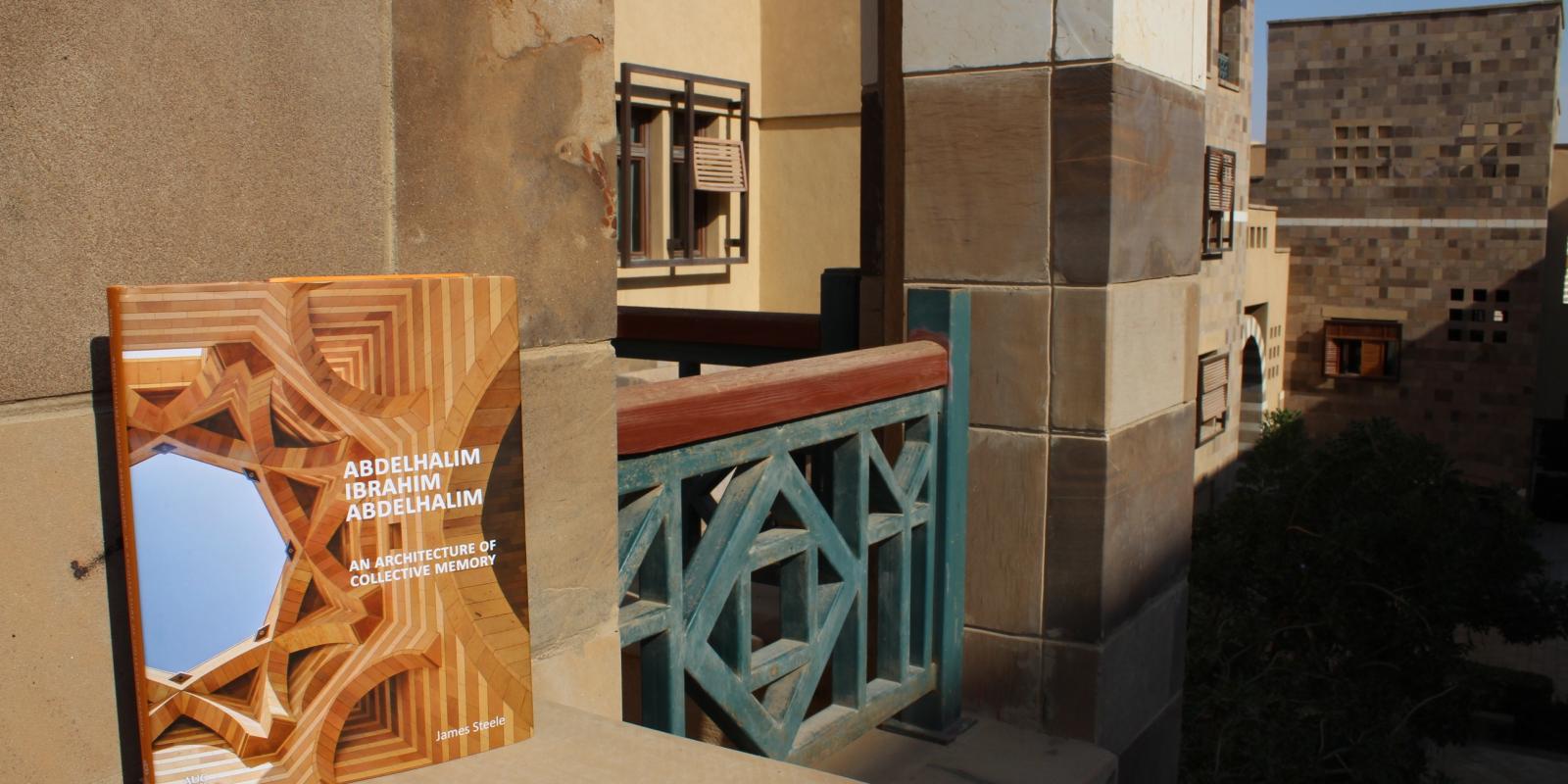

University leadership assembled an accomplished and diverse international team of architects to collaborate on the new campus project to prevent the University’s future development from being constrained by a single architectural vision. The finished campus would show each firm’s unique vision, but the process of working together would ensure there was harmony in the diversity. CDC AbdelHalim (Community Design Collaborative) from Egypt and Sasaki and Associates from Massachusetts, USA were selected as co-prime architects to lead the international team in executing the design and construction master plan for the new campus.

Central to the team’s vision of the campus master plan was the idea of linking physical space with AUC’s liberal arts philosophy, reflecting a pride in Egypt’s cultural history while also paving the way for the University community to take the lead in defining the spirit of the campus. In designing the new campus, the team sought to capture the international identity of the AUC community as well as the multidimensionality of the liberal arts curriculum in an architecturally diverse space.

Throughout the planning phase, it became increasingly obvious that this would not be a process of simply moving the old campus to a new location. The new campus – despite following the roots of AUC Tahrir Square – would have its own unique identity and would continue to evolve and mature over time. The outcome was a master plan with design principles for expansion strategically built into it.

The international team embarked on a meticulous journey of research and travel to explore Egypt’s unique architectural history as well as navigate the existing landscape of New Cairo. Inspired by Egypt’s history of advanced engineering practices, they revived traditional processes for cutting stone and sourced materials from Upper Egypt to build up the campus walls, bolstering the campus with the strength of a brilliant past.

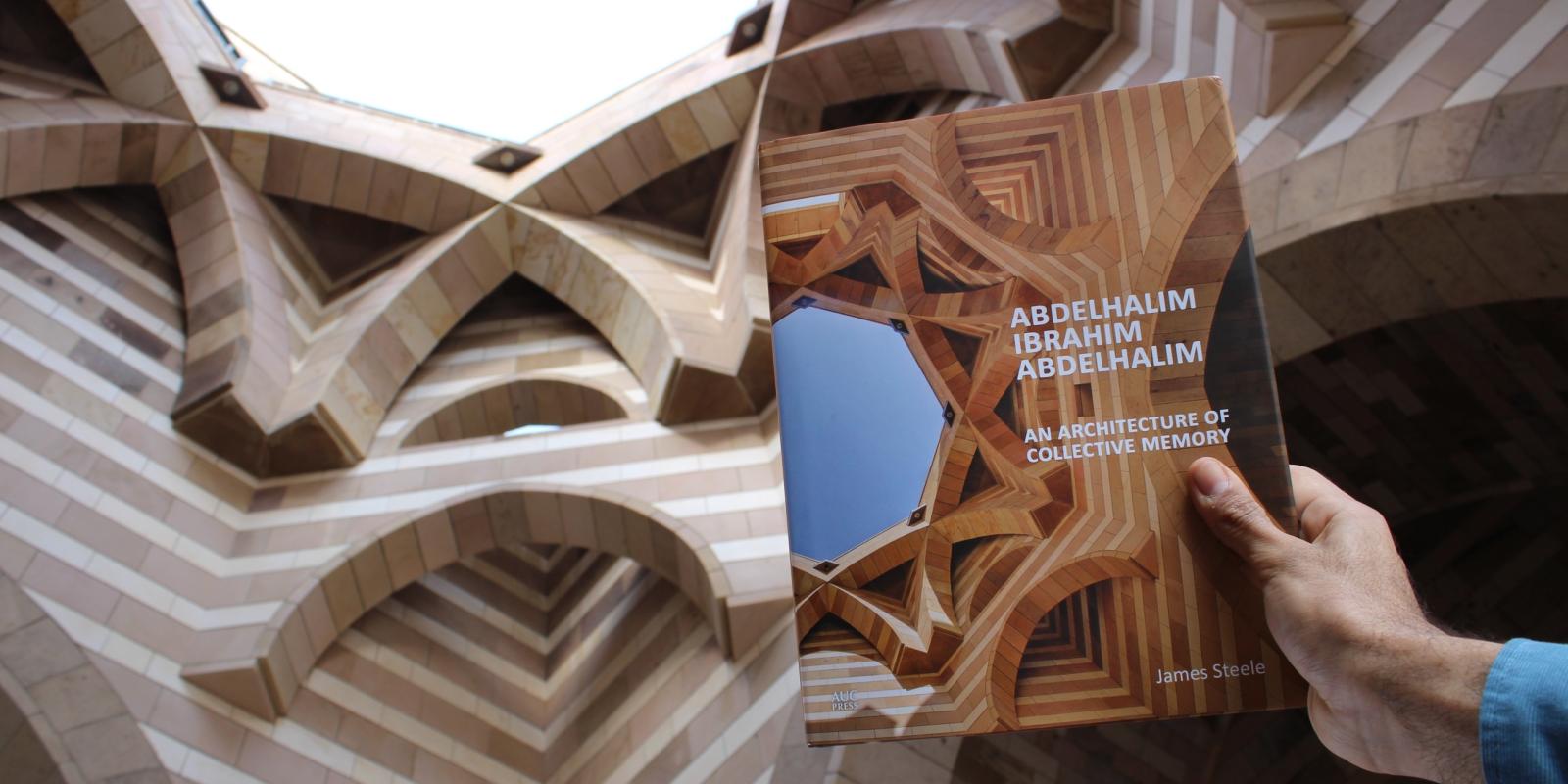

Welcoming visitors at the main entrance to campus is the AUC Portal. The architects drew primary inspiration for the structure from AUC Tahrir Square’s iconic arch – bringing a piece of the old campus to the University’s new home. Inspired by the crossed-arch dome of the Great Mosque of Córdoba in Spain, the Portal’s multiple arches became a representation of the liberal arts education, exemplifying the concept of reaching the truth through multiple sources. The structure was intentionally left uncovered, exposing the sky above it, to symbolize that beyond this gateway, the sky is the limit to what you can learn and create.

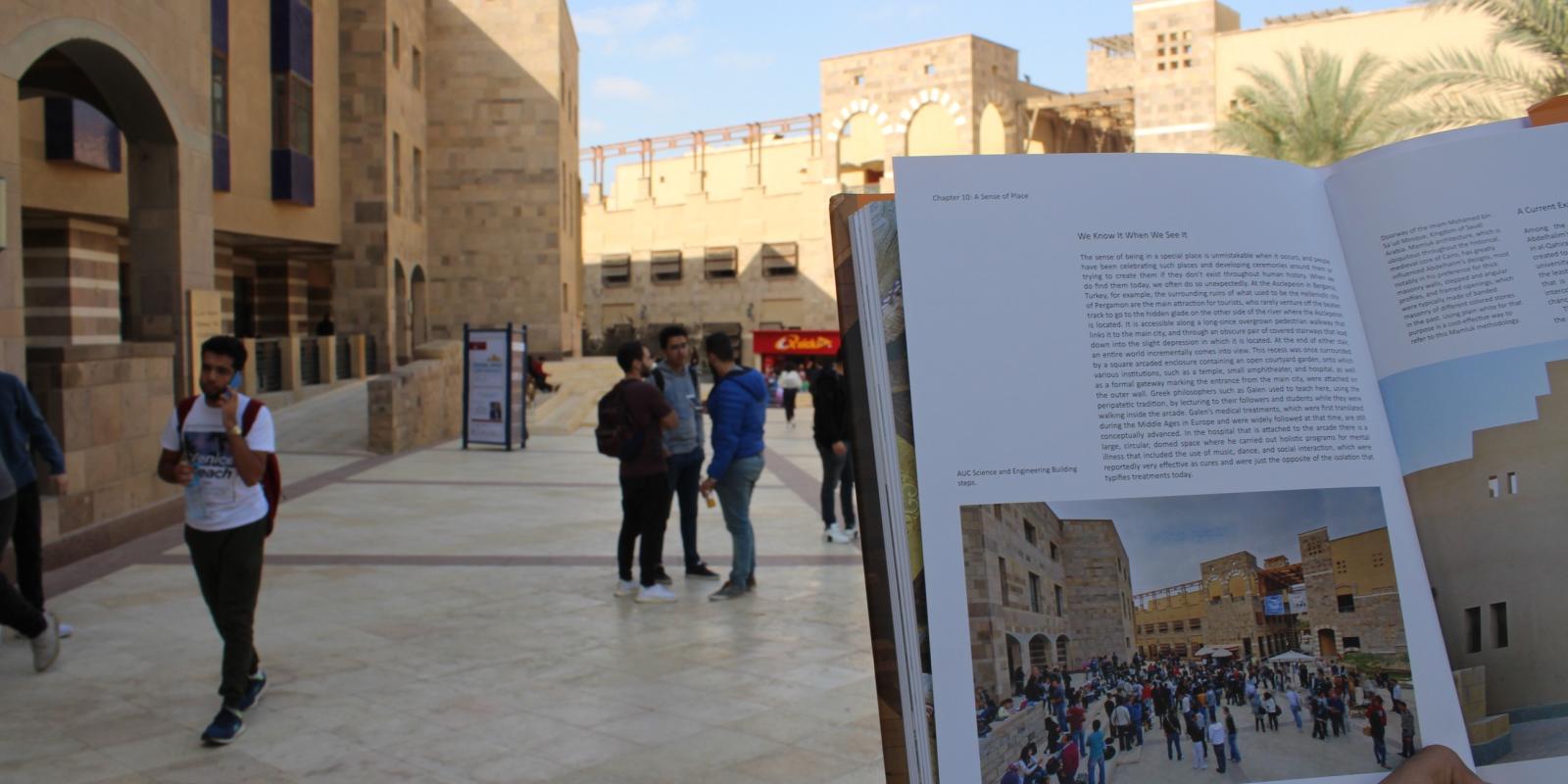

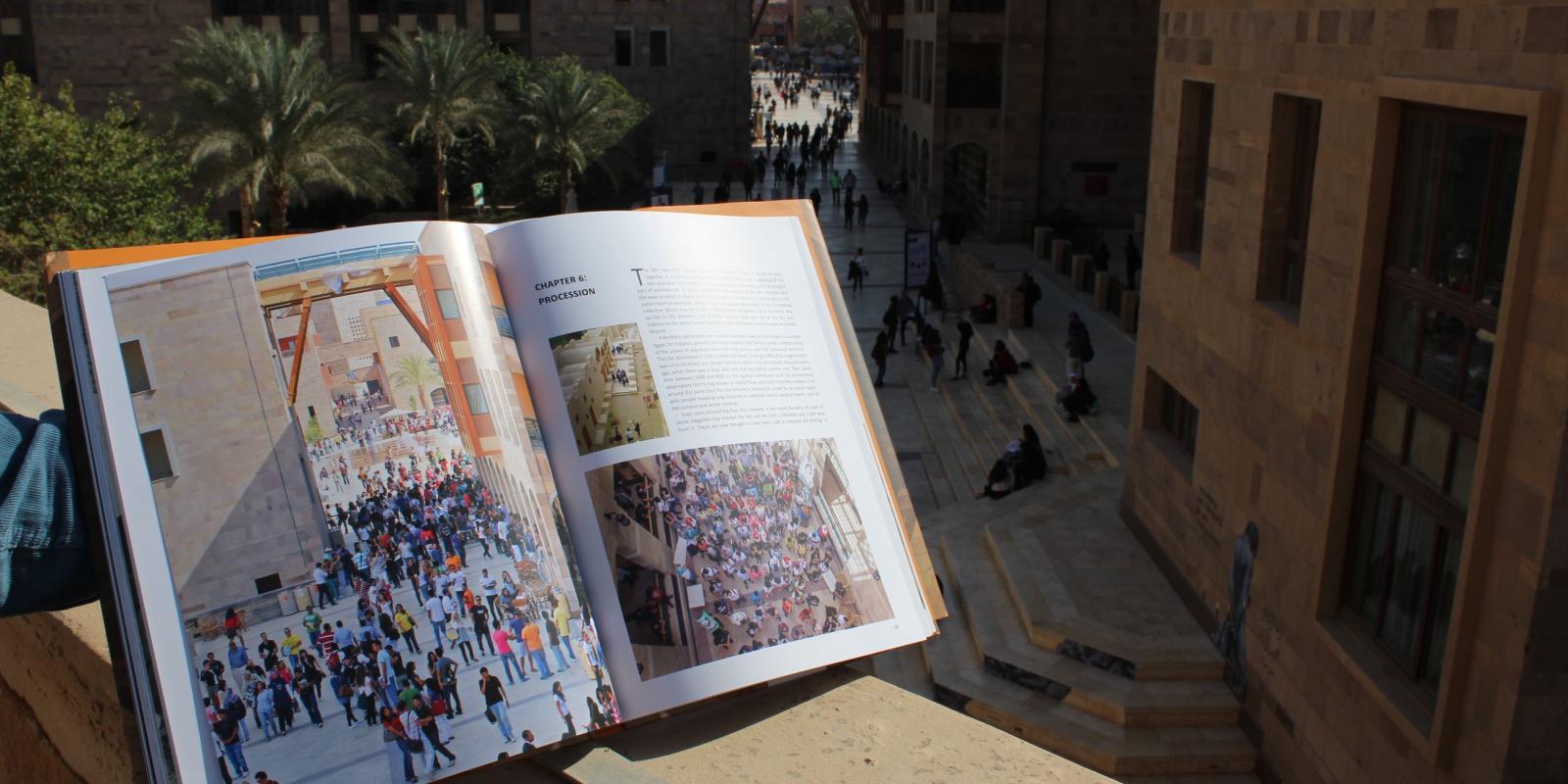

Across the campus, a continuous chain of enclosed spaces mirrors the rhythm and movement of campus life. Inspired by the traditional urban fabric of Egypt’s capital city – particularly Sharia Al Muizz in Islamic Cairo – the “campus spine,” as dubbed by the team of architects, interconnects these various branches of open space, acting as both a tribute to the desert landscape and providing a campus texture that allows for interchange and the evolution of a thriving University community. The archways that connect and support campus buildings, as well as the Mashrabiya-textured windows and structures, are rooted in traditions from Islamic art and architecture – a vital part of Egyptian cultural and religious history.

The campus is also sprinkled with architectural themes inspired by buildings in Spain, Italy, Iran, New Mexico, Arizona and the Mediterranean. Architect Ricardo Legorreta of Legorreta + Legorreta, who also designed the Campus Center, drew inspiration from his native Mexico when designing the boldly colored student residences. Reminiscent of a small town or village, the square buildings are nestled among palm groves, gardens and small courtyards, creating a private space that encourages community building among students.